Gratitude, Job Resources, and Job Crafting: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study on a Sample of Romanian Employees

[La gratitud, los recursos del puesto de trabajo y la adaptaci├│n del puesto al empleado: un estudio en dos momentos con una muestra de empleados rumanos]

Elena G. Nicuta1, Cristian Opariuc-Dan2, and Ticu Constantin1

1Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi, Romania; 2Ovidius University of Constanta, Romania

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a2

Received 23 April 2023, Accepted 9 October 2023

Abstract

In this two-wave study, we tested whether there would be positive and reciprocal relationships between employees’ gratitude and the job resources they perceive at work, as well as between gratitude and job crafting behaviours. Moreover, we explored whether job crafting could mediate the relationship between gratitude and job resources. The participants were 275 Romanian employees. No evidence for reciprocal relationships was found. Results showed that gratitude at T1 predicted more job resources at T2 (three months later), but job resources did not predict employees’ gratitude over time. One dimension of job crafting (increasing challenging job demands) at T1 positively predicted employees’ gratitude at T2, but the prospective effect of gratitude on job crafting was not significant (except for a marginally significant effect on increasing structural job resources). Job crafting did not mediate the longitudinal relationship between employees’ gratitude and job resources. These findings are discussed in relation to previous literature.

Resumen

En este estudio se probó en dos momentos distintos si había relaciones positivas recíprocas entre la gratitud de los empleados y los recursos que percibían en el trabajo, así como entre la gratitud y la adaptación del puesto de trabajo al empleado. También se exploró si la adaptación del puesto al empleado podría mediar la relación entre gratitud y recursos del puesto de trabajo. En el estudio participaron 275 empleados rumanos. No se demostró que hubiera relaciones recíprocas. Los resultados indican que la gratitud en T1 predecía más los recursos del puesto en T2 (tres meses después), pero estos no predecían la gratitud de los empleados a lo largo del tiempo. Una dimensión de la adaptación del puesto al empleado, endurecer las exigencias del puesto en T1 predecía en sentido positivo la gratitud de los empleados en T2, pero el efecto prospectivo de la gratitud en la adaptación del puesto a los empleados no era significativo, excepto un efecto marginalmente significativo en el aumento de los recursos estructurales del puesto. La adaptación del puesto al empleado no mediaba la relación longitudinal entre la gratitud de los empleados y los recursos del puesto de trabajo. Se comentan los resultados en relación con las publicaciones anteriores.

Palabras clave

Gratitud en el trabajo, Recursos sociales del puesto, Recursos estructurales del puesto, Adaptaci├│n del puesto al empleado, Teor├şa ÔÇťampliar y construirÔÇŁ, Modelo de exigencias-recursos del puestoKeywords

Workplace gratitude, Social job resources, Structural job resources, Job crafting, Broaden-and-build theory, Job demand-resources modelCite this article as: Nicuta, E. G., Opariuc-Dan, C., and Constantin, T. (2024). Gratitude, Job Resources, and Job Crafting: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study on a Sample of Romanian Employees. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(1), 19 - 30. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a2

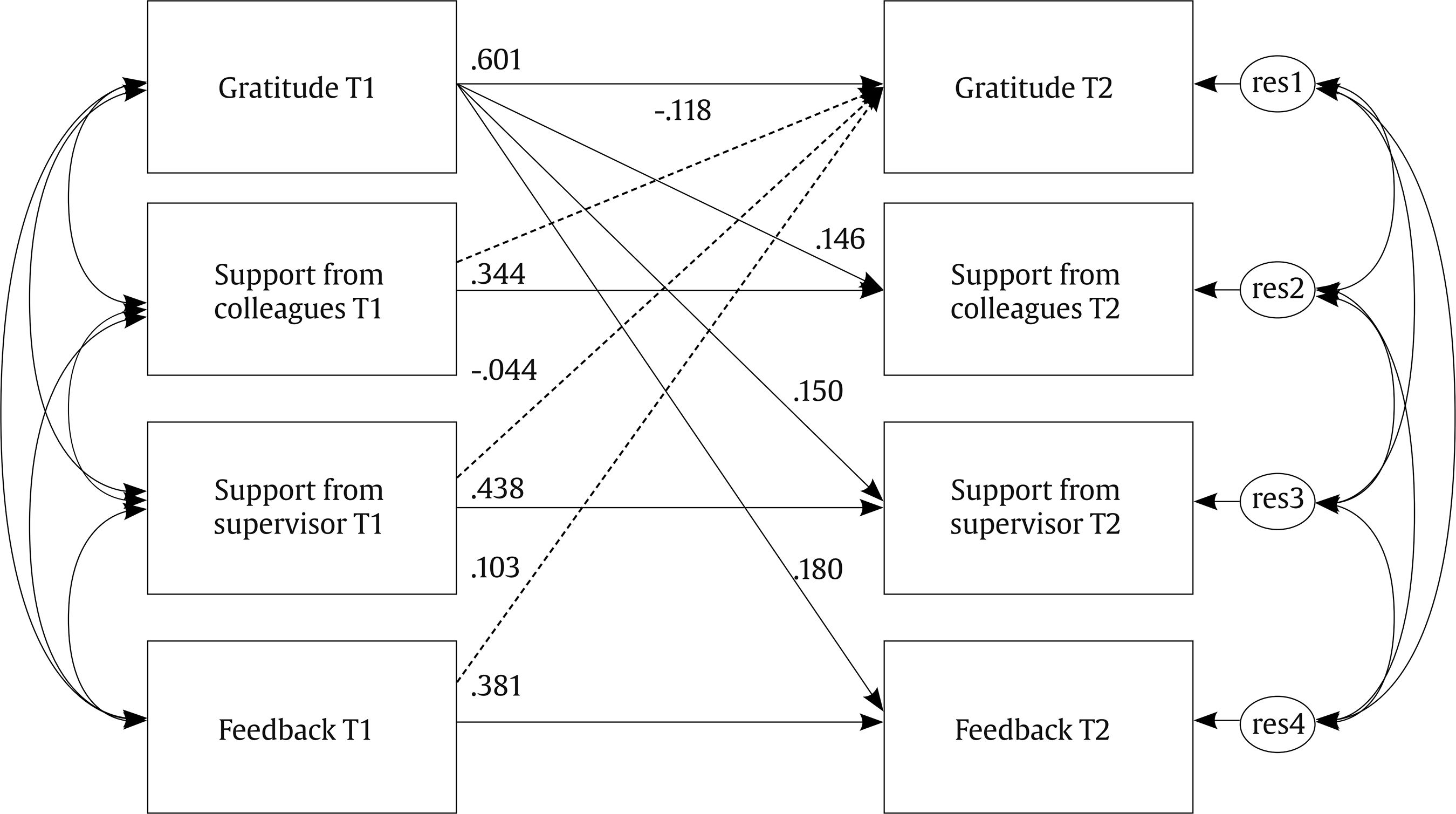

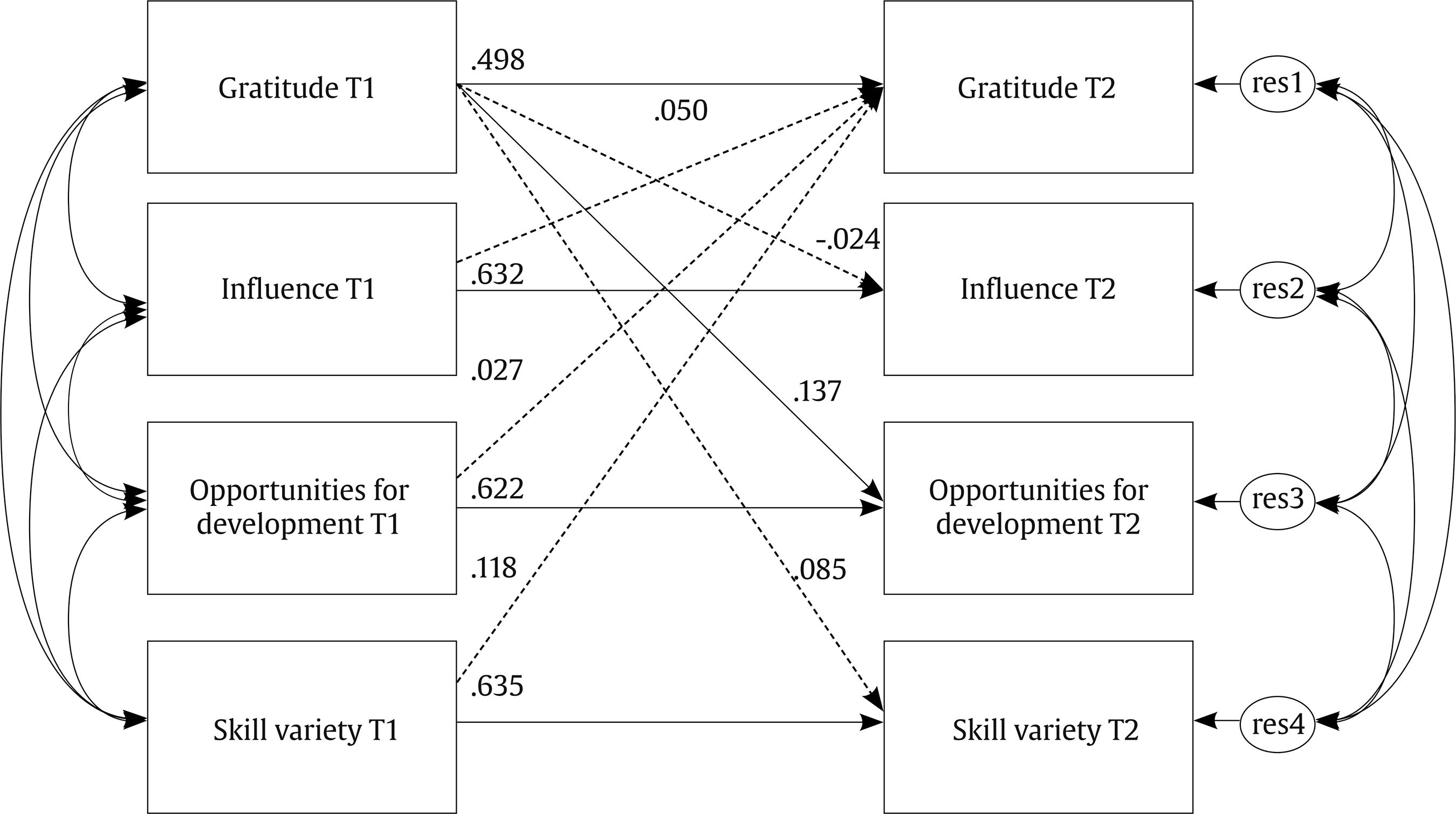

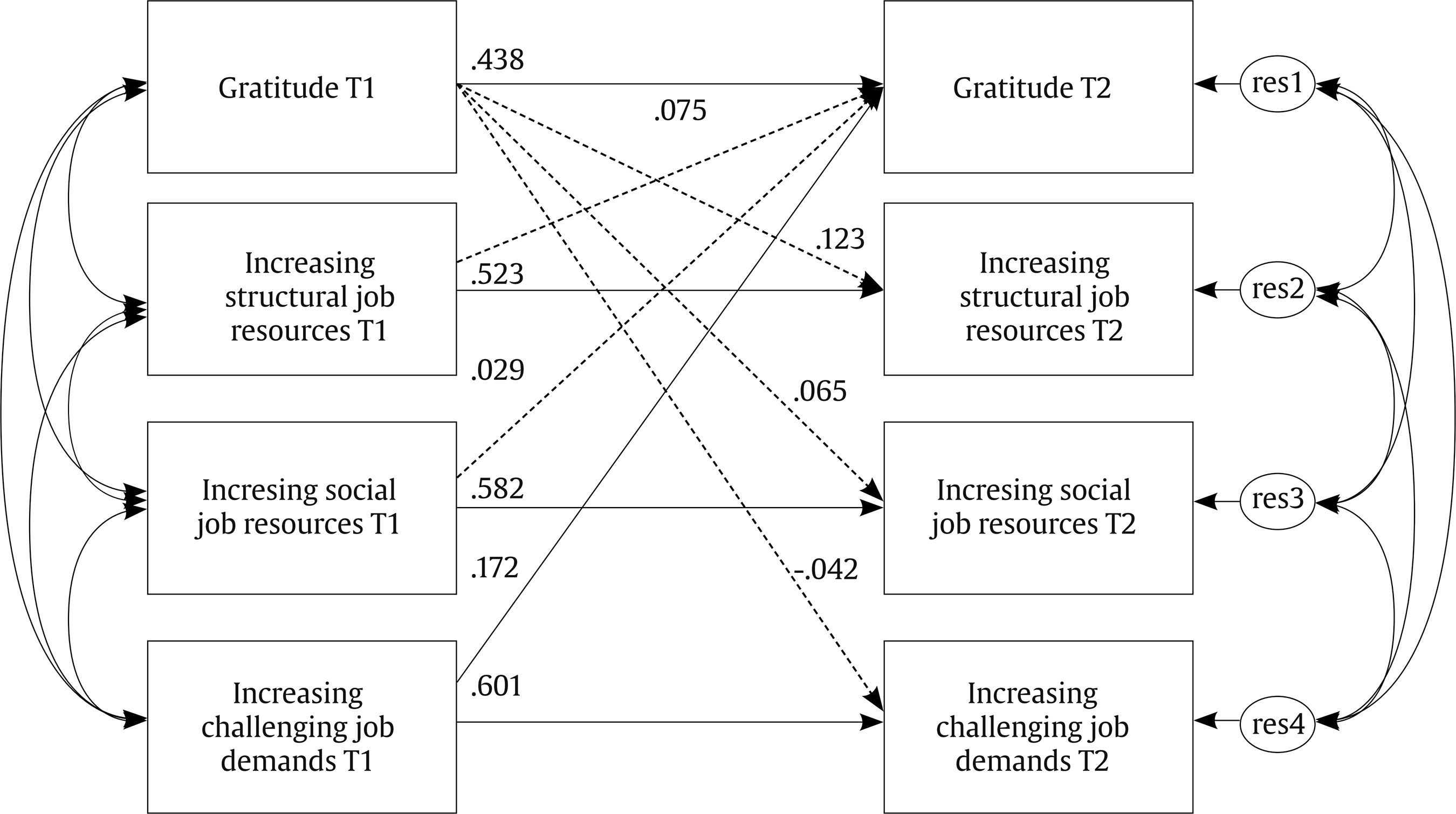

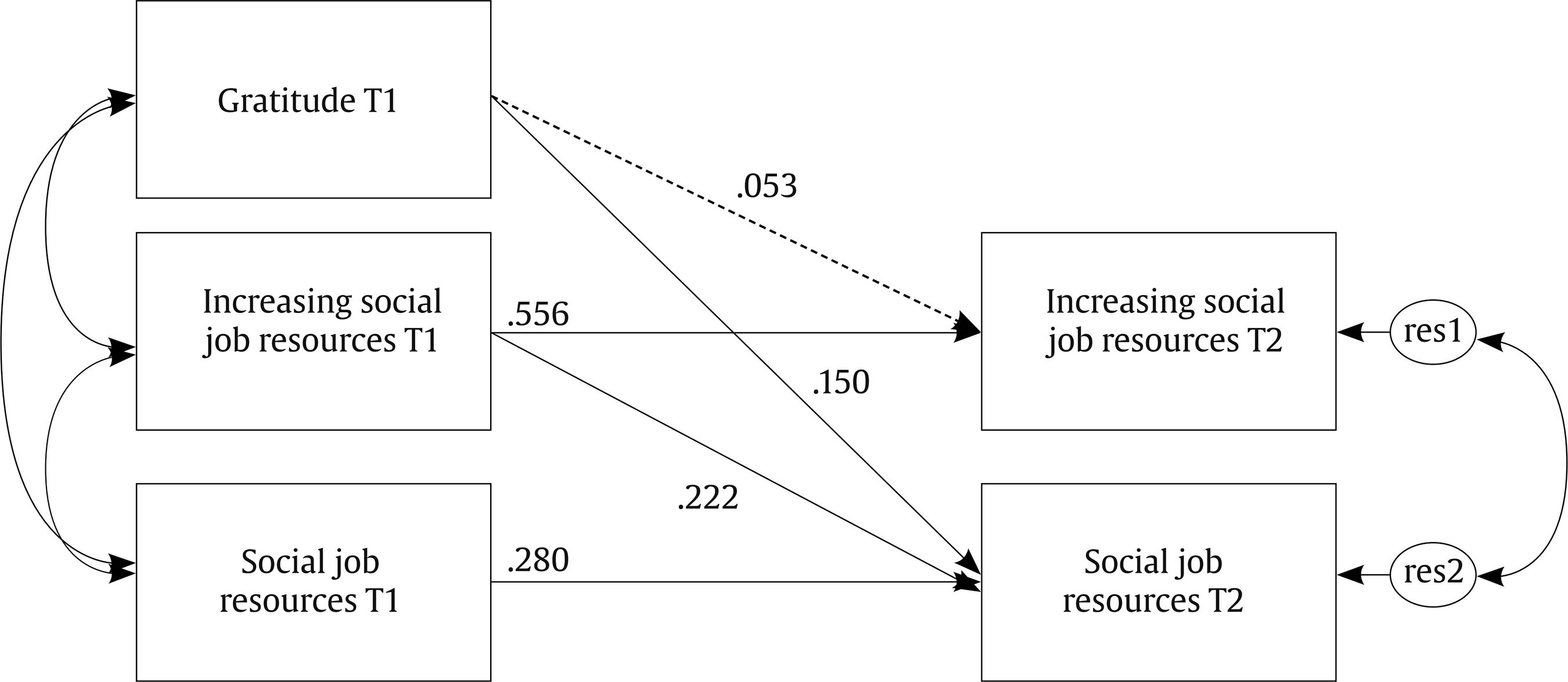

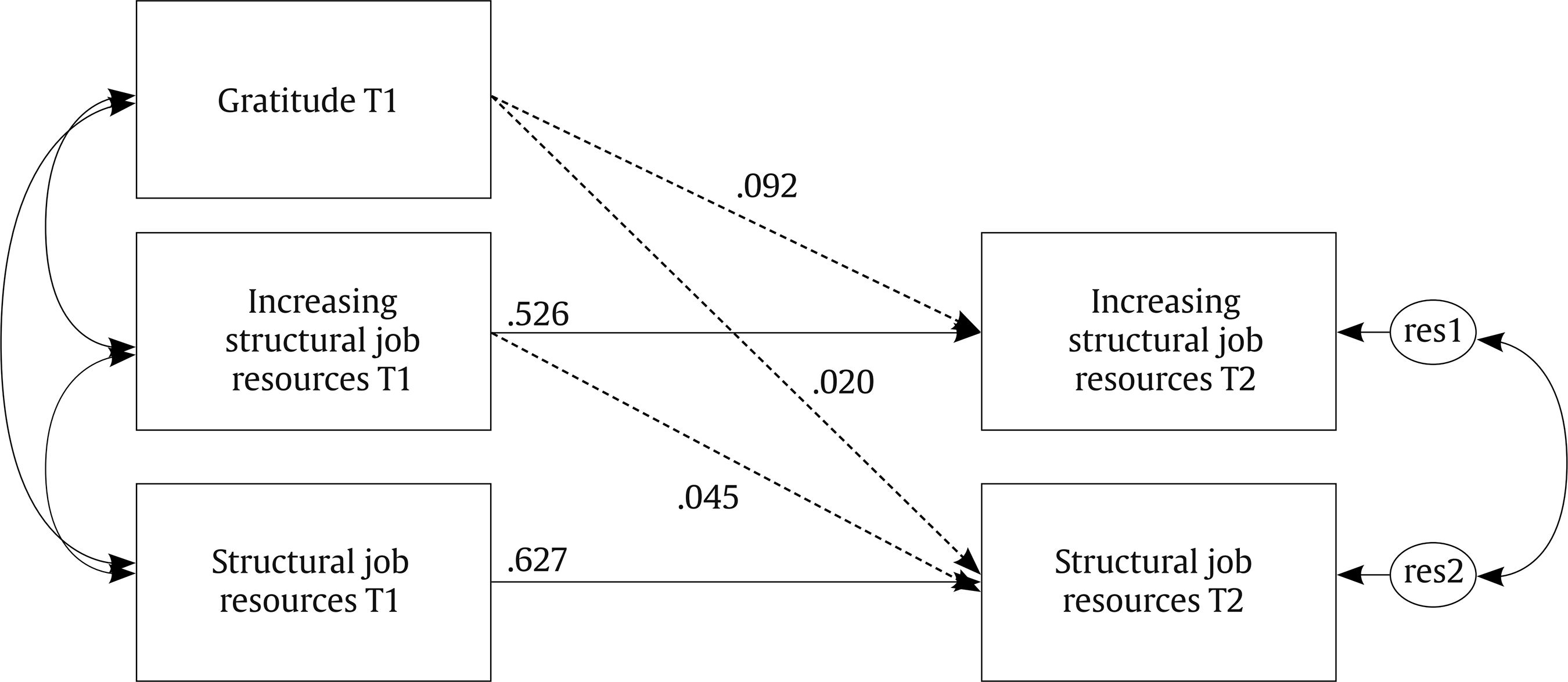

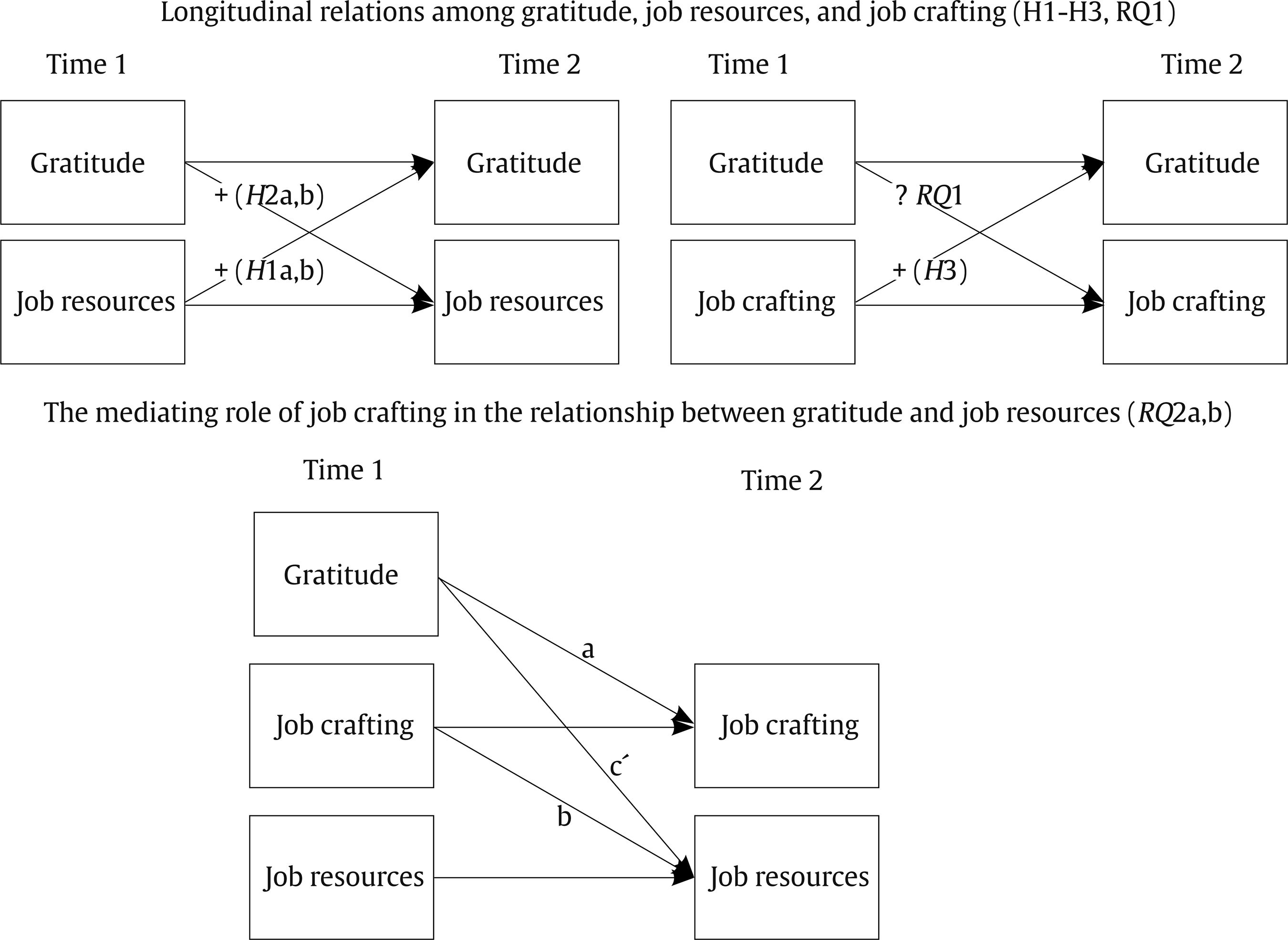

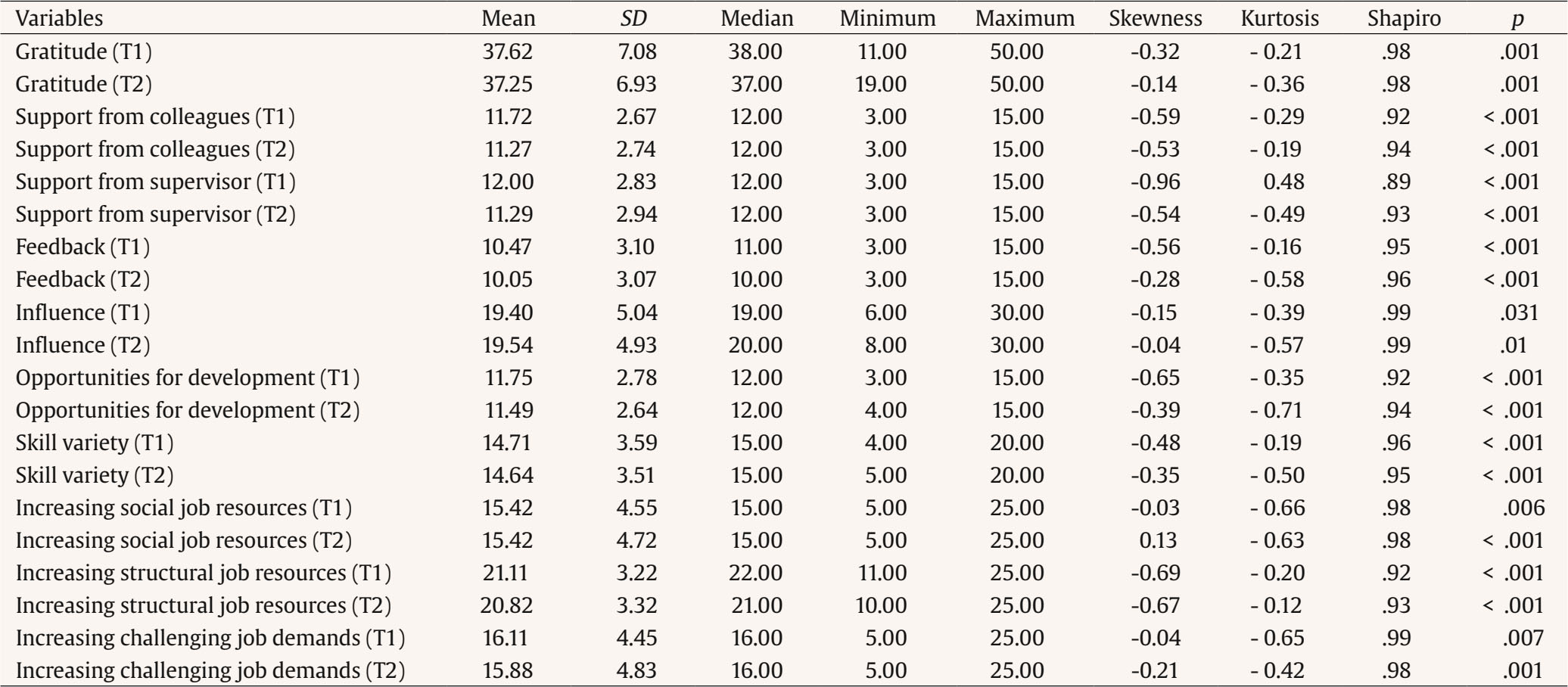

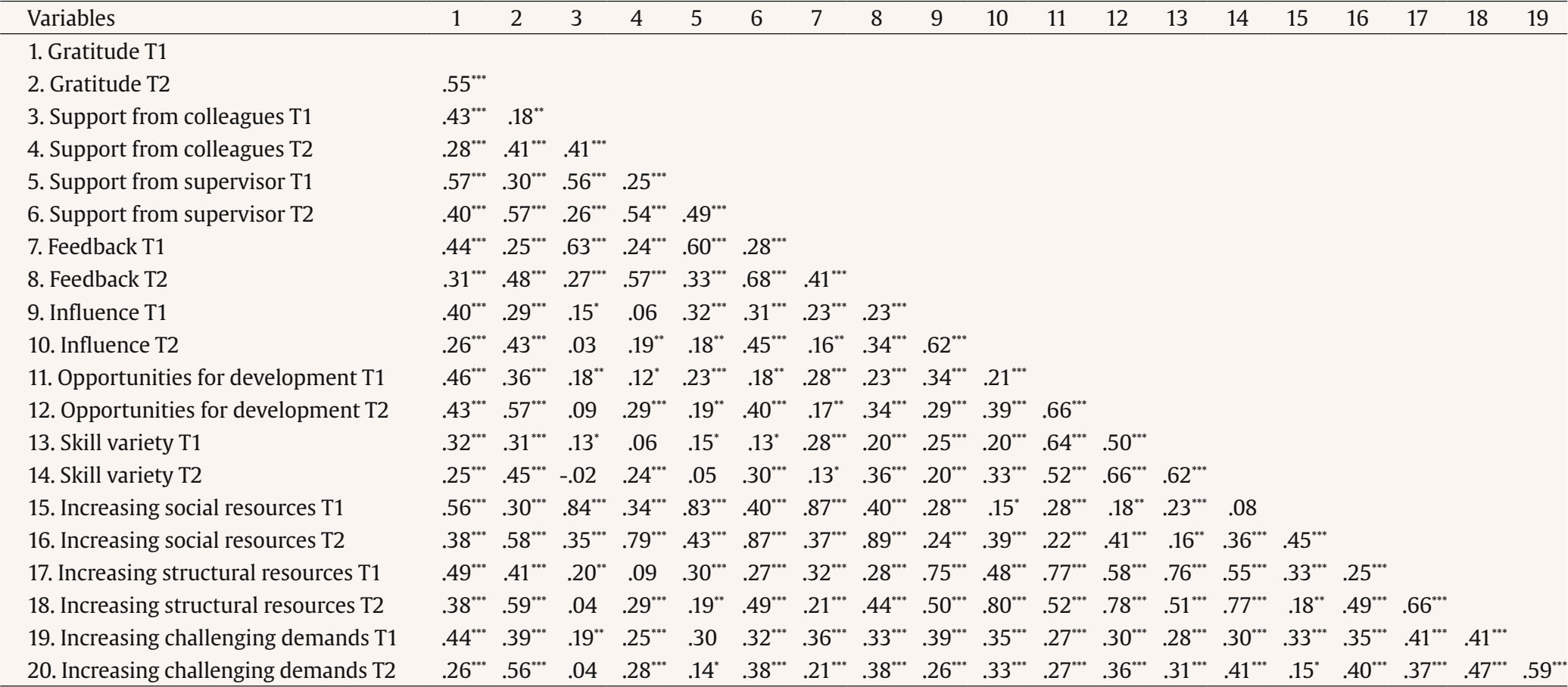

Correspondence: gabriela.nicuta@yahoo.com (E. G. Nicuta).Gratitude was previously shown to be linked to important positive outcomes for the employees and their organizations. Such benefits include increased job satisfaction, self-reported performance (e.g., Cain et al., 2019; Komase et al., 2020), as well as decreased burnout (e.g., Kersten et al., 2022; Nicuta et al., 2022). However, the exploration of this topic has just started in the literature (Locklear et al., 2022). Consequently, a number of important questions are unanswered. First, the antecedents of work-specific gratitude were rarely examined, as most studies focused on the consequences of gratitude. However, it is essential to uncover the determinants of gratitude before aiming to improve employees’ levels of thankfulness through various interventions. Moreover, although employees’ gratitude was found to be correlated with important attitudes and behaviours, the direction of these relationships still has to be determined, because most studies used cross-sectional and correlational designs. Therefore, additional research is needed in order to establish causality or, at least, the temporal precedence of gratitude in these relationships. This is a matter of utmost importance, seeing that otherwise the value of gratitude in the workplace might be overestimated. In this research, we focused on the relationship between employees’ work-specific gratitude, job resources, and job crafting. To our knowledge, only a few studies explored the associations between these variables and found thankfulness in the workplace to be positively correlated to both job resources and job crafting behaviours (e.g., Chen et al., 2021; Komase et al., 2020). We contribute to the literature by examining how gratitude relates to job resources and job crafting in a longitudinal study. Building on previous theoretical and empirical contributions, we examine whether there might be reciprocal relationships between these variables. Moreover, we explore whether job crafting behaviours could mediate the longitudinal relationship between gratitude and job resources. In the following paragraphs, we define gratitude in the workplace and review theoretical models and empirical evidence supporting the idea that employees’ gratitude might be both a consequence and a determinant of perceived job resources and job crafting behaviours. Defining Gratitude in the Workplace In the multilevel model of gratitude in the workplace, Fehr et al. (2017) distinguished between episodic, persistent, and collective gratitude. Situated at the event level, episodic gratitude is a short-lived positive emotional experience that occurs when employees attribute a beneficial outcome to someone other than themselves. At the individual level, persistent gratitude refers to one’s predisposition to feel grateful within contexts related to their job. Persistent gratitude can therefore be understood as an emotion schema that increases employees’ attentiveness to the positive aspects of their work context, as well as their tendency to recall such gratitude-inducing experiences. Employees likely develop persistent gratitude as a result of repeatedly experiencing episodic gratitude in the workplace. Lastly, collective gratitude occurs at the organizational level when employees have similar levels of persistent gratitude and thankfulness is shared within the organization. In the present research, we focused on persistent gratitude, which has a more lasting impact compared with episodic gratitude and influences the way employees perceive and react to a variety of situations (Fehr et al., 2017). The Reciprocal Relationship between Employees’ Gratitude and Job Resources The Effect of Job Resources on Employees’ Gratitude Job resources can be defined as valuable components of a job that help employees achieve work-related goals, encourage workers’ self-improvement and development, while also protecting them from the negative consequences of increased job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Previous literature suggests that there are two broad types of job resources – structural job resources, which are more closely tied to job design (e.g., the autonomy and opportunities for development that employees have in their jobs) and social job resources, which refer to the interpersonal aspects of the work environment (e.g., the support and feedback employees receive from others in the workplace) (Tims et al., 2012). Both structural and social job resources are important antecedents of a number of positive outcomes in the workplace. Previous studies found that employees who perceive more resources in their work environment tend to be more satisfied with their jobs (e.g., Liu et al., 2023; Solomon et al., 2022) and to report higher levels of work engagement (see Mazzetti et al., 2023 for a meta-analysis). In this study, we posit that job resources could also be a determinant of employees’ gratitude. According to the social-cognitive theory of trait and state gratitude (Wood, Maltby, Stewart, et al., 2008), a benefit elicits gratitude when it is perceived as valuable, costly to provide, and altruistically intended. At least two of these three criteria should be met by job resources. Seeing that job resources are of crucial importance for task completion and goal attainment, they should be perceived as valuable by the employees. Moreover, job resources involve various costs for the company/the co-worker providing them (e.g., giving individual feedback is time-consuming for the manager). Some job resources are offered out of a sincere desire to help (without ulterior motives), although organizations naturally anticipate a return on their investment from the employees’ side (i.e., high performance). It is therefore reasonable to expect that employees who have access to more job resources will repeatedly experience higher levels of episodic gratitude in the workplace, which will over time result in their overall predisposition to be more grateful for their jobs (i.e., higher levels of persistent gratitude; Fehr et al., 2017). In Komase et al.’s (2020) cross-sectional study, the authors found that perceived job control and social support were positively correlated to employees’ work-specific gratitude. Whether other types of job resources might also result into increased levels of employees’ thankfulness for their jobs still has to be determined. In order to advance the literature, we aimed to examine the longitudinal effect of three social job resources (i.e., social support from the supervisor, social support from the co-workers, and feedback) and three structural job resources (i.e., influence, opportunities for development, and skill variety) on employees’ gratitude. In line with the previous theoretical and empirical contributions presented above, we hypothesized that: H1a: Social job resources would prospectively predict increased levels of employees’ gratitude. H1b: Structural job resources would prospectively predict increased levels of employees’ gratitude. The Effect of Employees’ Gratitude on Job Resources Various theoretical contributions support the idea that gratitude helps people create and maintain social resources. According to the find-remind-and-bind theory (Algoe, 2012), gratitude (1) helps people find high-quality interpersonal connections, (2) reminds them of current responsive interaction partners, and (3) binds people together, solidifying existing relationships. Moreover, gratitude was conceptualized as a moral emotion (Greenbaum et al., 2020; McCullough et al., 2001) and should act as a moral motive. People high in state and trait gratitude were shown to be more motivated to behave prosocially not only towards their initial benefactor (direct reciprocity), but also toward third parties (indirect reciprocity) (see Ma et al., 2017, for a meta-analysis). By making people more inclined to act in an altruistic manner, gratitude should consolidate their social network. There is also empirical evidence to support the idea that gratitude generates social resources. A study conducted by Wood, Maltby, Gillett, et al. (2008) found evidence for the prospective effect of gratitude on social support in a sample of students. Their results suggest that gratitude at the beginning of the semester predicted social support at the end of the semester, three months later. More recently, D. Wang et al. (2022) reported similar results. In their longitudinal study, gratitude predicted perceived social support in a sample of Chinese adolescents who were exposed to the Wenchuan earthquake. A number of studies conducted in the work context also argued that trait gratitude helps employees build more social resources in their jobs (e.g., Chen et al., 2021; Feng & Yin, 2021; Nicuta et al., 2022). Although these studies found that gratitude positively predicted social support, they did not measure work-specific gratitude and were not longitudinal. Therefore, the temporal precedence of gratitude could not be established. In order to add to the literature, we aimed to examine whether comparable results would be obtained using a longitudinal design. Consistent with existing theoretical and empirical evidence, we hypothesized that: H2a: Employees’ gratitude would prospectively predict increased social resources. Assuming that gratitude in the workplace will lead to more social resources, one might wonder whether employees’ gratitude will also influence structural job resources. According to Fredrickson’s (2004) broaden-and-build theory, gratitude is a positive emotion. As opposed to negative emotions, which narrow one’s thought-action repertoire and are associated with specific action tendencies (e.g., fight-or-flight response), gratitude should expand employees’ attention, cognition, and behaviour. By being more receptive to their environment, grateful employees might become more aware of the structural resources that are at their disposal and that others might overlook. Moreover, based on the theoretical view that gratitude is a moral emotion that motivates people to reciprocate the benefits they received (McCullough et al., 2001), we argue that people who experience high levels of gratitude in their workplace might seek ways to repay their companies. One way employees can do that is by taking on additional tasks aimed at their professional development and by demonstrating increased work engagement, which ultimately result in more structural job resources (such as autonomy or opportunities for professional development). Therefore, we expected that: H2b: Employees’ gratitude would prospectively predict more structural resources. The Reciprocal Relationship between Gratitude and Job Crafting The Effect of Job Crafting Behaviours on Gratitude In line with Tims and Bakker (2010), we define job crafting as the proactive behaviours undertaken by employees in order to adjust the levels of job demands and resources they experience in their jobs. Tims and Bakker initially proposed that job crafting comprises four dimensions: a) increasing social job resources (e.g., asking others for advice), b) increasing structural job resources (e.g., learning new skills), c) increasing challenging job demands (e.g., voluntarily taking on additional responsibilities), and d) decreasing hindering job demands (e.g., trying to reduce mental or emotional workload). However, in a meta-analysis conducted by Rudolph et al. (2017), decreasing job demands loaded poorly on the latent job crafting factor, casting doubt on whether it should be included as a job crafting dimension. Therefore, in this study, when referring to job crafting, we only take into consideration the first three of the four dimensions which were presented by Tims and Bakker. According to the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), employees who are active crafters of their jobs will have improved motivation, occupational well-being, and job performance. Empirical research substantiates this idea, indicating that job crafting has numerous benefits. For example, it was shown to be positively linked to employees’ work engagement, job satisfaction, and positive affect, while being negatively related to burnout (see Boehnlein & Baum, 2022; Frederick et al., 2020, for meta-analyses). In this study, we argue that job crafting behaviours could increase employees’ thankfulness as well. According to Wrzesniewski & Dutton (2001), job crafting behaviours are one of the ways in which employees can fulfil their basic needs for autonomy, self-enhancement, and connectedness. In fact, some studies indicate that the relationship between job crafting and employee well-being is mediated by basic psychological needs satisfaction (Toyama et al., 2022; L. Wang et al., 2022). Employees who craft their jobs to a larger extent report increase need satisfaction, which in turn predicts higher levels of positive emotions, positive psychological functioning, as well as work engagement. Seeing that basic psychological need satisfaction is an important predictor of gratitude (e.g., Datu & Fincham, 2022; L.-N Lee et al., 2015), it seems plausible that job crafting could also result in increased gratitude. Given these past findings, we hypothesized that: H3: Job crafting would prospectively predict increases in employees’ gratitude in the workplace. The Effect of Gratitude on Job Crafting The broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2004) was used in prior studies to explain why positive emotions could determine job crafting behaviours. As described above, this theory argues that positive emotions promote cognitive flexibility and motivate people to engage in activities that might result in increased personal resources. Therefore, it could be argued that employees who experience positive emotional states at work might be more predisposed to proactively and creatively redesign various aspects of their work. In line with this view, Rogala and Cieslak (2019) reported that positive emotions at work predicted employees’ job crafting behaviours. Chen et al. (2021) proposed that gratitude, being a positive emotion, should also broaden employees’ thought-action repertoire and that job crafting is one of the ways in which grateful employees’ proactivity could manifest itself. They found a positive correlation between trait gratitude and job crafting. In Chen et al.’s research, job crafting was defined as comprising the three dimensions of task, relationship, and cognitive crafting, in line with the work of Wrzesniewski and Dutton (2001). To extend the literature, we aimed to examine the association between gratitude and job crafting conceptualized from the perspective of the JD-R model (Tims & Bakker, 2010). Based on the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, as well as the empirical evidence presented above, we could expect gratitude to prospectively predict more job crafting behaviours. On the other hand, previous literature emphasized that job crafting behaviours originate from person-job misfit (Tims & Bakker, 2010; H. Wang et al., 2016). Otherwise put, employees are more likely to proactively change aspects of their jobs when they experience an imbalance between the demands of the job and their skills or between the resources they are provided with at work and their needs. Seeing that employees’ gratitude at work seems to stem from a strong person-job fit (i.e., employees are content with the resources and demands of their jobs), it could be inferred that grateful employees might be less motivated to craft their jobs. This is because they already find the current conditions of their jobs to be suitable and might not, as a result, be motivated to seek changes. In that respect, gratitude at work might be similar to job satisfaction. In a longitudinal study, Hakanen et al. (2018) found that, as opposed to work engagement, which prospectively predicted more job crafting behaviours, job satisfaction did not result in more job crafting. The authors argued that, although both work engagement and job satisfaction were experienced as positive, pleasurable states, work engagement was characterized by high activation, whereas job satisfaction was not. Likewise, gratitude might be experienced as a low activation positive state and might therefore be unrelated to job crafting behaviours. Given these conflicting perspectives, a research objective of our study was to examine the effect of gratitude on job crafting behaviours (RQ1). No specific hypothesis regarding this relationship was formulated. The Mediating Role Job Crafting in the Relationship between Gratitude and Job Resources Although gratitude at work and job resources were previously shown to be correlated (e.g., Komase et al., 2020), the underlying explanatory mechanism was never investigated. In this study, we sought to explore whether job crafting behaviours might explain why grateful employees report having access to more job resources. As previously argued in this paper, some theoretical perspectives (the broaden-and-build theory; Fredrickson, 2004) and empirical findings (Chen et al., 2021) suggest that gratitude might encourage employees to actively shape their work environment through job crafting behaviours. Further, according to JD-R theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), job crafting behaviours should help employees create more job resources. Empirical studies support this idea, indicating that employees who use job crafting report more social and structural resources (see Holman et al., 2023, for a meta-analysis). Therefore, in this study, we aimed to explore whether increasing social resources (as a dimension of job crafting) would mediate the longitudinal relationship between gratitude and social job resources (RQ2a), whereas increasing structural resources would mediate the relationship between gratitude and structural job resources (RQ2b; see Figure 1 for an overview of the research objectives and hypotheses). Participants and Procedure The study was approved by the institutional Research Ethics Committee (no. 592). Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. Participants were recruited by Psychology undergraduate students in exchange for course credit. Students, who were unaware of the researchers’ hypotheses, were instructed to invite up to four employees to take part in the research. Potential participants had to be over 18 years old and to be employed (regardless of the type of contract – full time or part-time) in order to be eligible for the study. Informed consent was obtained from those who volunteered to participate. Initially, 427 employees filled in the questionnaires. In the second wave of the study (i.e., three months later1), 275 participants (64.4 % of the initial sample) agreed to complete the questionnaires again. The majority of participants in the final sample were female (62.9 %). They were aged between 18 and 66 years old (M = 32.49, SD = 12.19). In terms of education, 2.9 % had lower than a high-school diploma, 45.1% of the participants had a high-school diploma, 37.1% had a bachelor’s degree, and 14.9% had a master’s degree or higher. On average, participants had been working for their current organization for 5.75 years (SD = 7.37). The majority of employees in our sample (66.5%) worked in the private sector and had full-time jobs (90.2%). Participants worked in a variety of industries, including human resources, customer relations, hospitality, education, healthcare, computer and technology, etc. Measures For all questionnaires included in the present study, items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never/completely disagree, 5 = always/completely agree). The scales were administered in Romanian. To ensure that the Romanian version of the instruments was equivalent to the original (English) version, the back-translation technique was used. The questionnaires (including the items, the instructions for the participants, and the response scales) were first translated into Romanian by a bilingual organizational psychology researcher. The Romanian versions of the questionnaires were then translated into English by a different translator (another Romanian organizational psychologist who was also proficient in English). The original and back-translated versions were compared and items with inaccurate back-translations were revised. Gratitude at Work Employees’ predisposition to feel gratitude at work was measured with the Gratitude at Work Scale (Cain et al., 2019). Participants were asked to think about their current job and indicate how often they felt grateful for various aspects of their job. In the studies reported by Cain et al. (2019), exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses suggested that the instrument measures two distinct dimensions, namely Gratitude for Meaningful Work (4 items; e.g., “... your own accomplishments at work?”) and Gratitude for a Supportive Work Environment (6 items; e.g., “ ...the atmosphere/climate of your work environment?”). However, a previous study found that the Romanian version of the scale is unidimensional (Nicuta, 2021). Therefore, we calculated a total score by adding up all items (α = .91, 95% CI [.89, .92]). Social Resources The social resources evaluated in this study were social support from the colleagues, social support from the supervisor, and feedback. Social support from colleagues (3 items; e.g., “Your colleagues are willing to listen to your problems at work, if needed.”; α = .87, 95% CI [.85, .89]) and social support from the supervisor (3 items; e.g., “You get help and support from your immediate superior, if needed.”; α = .87, 95% CI [.84, .89]) were evaluated with slightly modified items from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ; Burr et al., 2019). Received feedback was measured with the Feedback from others scale from the Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006) (3 items; e.g., “You receive a great deal of information from your manager and co-workers about your job performance.”; α = .86, 95% CI [.84, .89]). For the mediation analyses, a total score was calculated by summing up all items measuring social resources, α = .92, 95% CI [.90, .93]. Structural Resources Influence, opportunities for development, and skill variety were the three structural job resources measured in this study. Influence (6 items; e.g., “You have a large degree of influence on the decisions concerning your work.”; α = .88, 95% CI [.85, .90]) and opportunities for development (3 items; e.g. “Your work gives you the opportunity to develop your skills.”; α = .88, 95% CI [.86, .90]) were measured with scales from the COPSOQ (Burr et al., 2019). Skill variety (3 items; e.g., “Your job requires you to use a number of complex or high-level skills.”; α = .92, 95% CI [.91, .94]) was measured with a scale from the WDQ (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). For the mediation analyses, a total score was calculated by summing up all items measuring structural resources (α = .92, 95% CI [.90, .93]). Job Crafting Job crafting behaviours were measured with the Job Crafting Scale (Tims et al., 2012). Three subscales from the original questionnaire were used in this study: a) increasing structural job resources (5 items; e.g., “I try to learn new things at work”; α = .87, 95% CI [.83, .88]), b) increasing social resources (5 items; e.g., “I ask my supervisor to coach me.”; α = .87, 95% CI [.85, .89]), and c) increasing challenging job demands (5 items; e.g., “I regularly take on extra tasks even though I do not receive extra salary for them" α = .89, 95% CI [.87, .91]). A total score was calculated for each job crafting dimension by summing up its respective items. Overview of the Analyses We used R (R Core Team, 2022b) for all our analyses2. First, preliminary analyses were performed. Descriptive statistics were computed and we used the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess univariate normality. Data was screened for outliers and the Mardia indicator was used to assess multivariate normality. Second, we analysed the associations among the main study variables. Third, path analyses were used to test the hypotheses. The data and code used to generate the results presented below are openly available at https://osf.io/vsjah/?view_only=d39345059a874f65804ca9ffad3ca631. Preliminary Analyses Descriptive statistics for the main study variables are presented in Table 1. None of the variables met the assumption of univariate normality. Outliers were identified for some of the variables; however, no extreme values were found. Our results further suggested that the multivariate normality assumption was not met. We first tested the multivariate normality assumption for the eight variables which were to be used in the path analysis concerning the relationship between gratitude and social job resources. Mahalanobis distances were situated between 0.89 and 6.04, with the multivariate distribution being both skewed (Mardia = 6.23, skewness = 285.37, p < .001) and leptokurtic (Mardia = 95.73, kurtosis = 10.31, p < .001). The second analysis included gratitude and each of the three structural job resources (T1 and T2). The Mahalanobis distances were situated between 0.80 and 5.27 and the multivariate distribution was skewed (Mardia = 4.76, skewness = 218.03, p < .001) and leptokurtic (Mardia = 90.29, kurtosis = 6.75, p < .001). Finally, the third analysis included gratitude and the dimensions of job crafting, measured at T1 and T2. Mahalanobis distances were situated between 1.06 and 5.49 and the multivariate distribution was again both skewed (Mardia = 4.57, skewness = 209.24, p < .001) and leptokurtic (Mardia = 92.06, kurtosis = 7.91, p < .001). Given the results of the preliminary analyses, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to compute the associations between the variables. We also decided to use the diagonally weighted least squares estimator for the path analyses. Associations among the Study Variables Correlations among the main variables are displayed in Table 2. With very few exceptions, the associations were positive and statistically significant. Gratitude (at T1 and T2) was positively related to all job resources (measured at T1 and T2), as well as to the three dimensions of job crafting (at T1 and T2). Job resources (at T1 and T2) were positively correlated with job crafting (at T1 and T2). Path Analyses Testing the Hypotheses The Relationships between Employees’ Gratitude and Social Job Resources First, we examined longitudinal relationships between employees’ gratitude and social job resources. The model (see Figure 2) demonstrated excellent fit, χ2(6) = 0.94, p = .98, CFI = 1, SRMR = .01, RMSEA = .00, p = .99, 90% CI [.00, .00]. All variables measured at T1 significantly predicted their T2 counterparts. We found no support for hypothesis H1a, as the support employees received from their supervisors and the feedback they reported at time 1 did not predict employees’ gratitude at time 2. Moreover, the support from the colleagues at T1 had a marginally significant and negative effect on employees’ gratitude at T2 (B = - 0.31, z = -1.77, p = .08, β = - .12). However, in line with hypothesis H2a, the results indicated that gratitude at time 1 predicted support from the supervisor (B = 0.06, z = 2.08, p = .04, β = .15), support from the colleagues (B = 0.06, z = 2.19, p = .03, β = .15), and feedback at time 2 (B = 0.08, z = 2.70, p = .01, β = .18). Figure 2 Path Model Examining the Longitudinal Relationships between Gratitude and Social Job Resources.Standardized coefficients. Significant paths are depicted as solid lines. Non-significant paths are represented by dotted lines.   The Relationships between Employees’ Gratitude and Structural Job Resources The relationships between employees’ gratitude and structural job resources were tested in a separate analysis. The model (see Figure 3) fitted the data well, χ2(6) = 1.72, p = .94, CFI = 1, SRMR = .01, RMSEA = .00, p = .99, 90% CI [.00, .01]. The autoregressive paths were significant. The results indicated that none of the structural resources measured at T1 predicted employees’ gratitude at T2, lending no support to hypothesis H1b. Nonetheless, the data provided partial support to hypothesis H2b, seeing that gratitude at T1 positively predicted opportunities for development at T2 (B = 0.05, z = 2.34, p = .02, β = .14). The relationship between gratitude at T1 and skill variety at T2 was marginally significant (B = 0.04, z = 1.66, p = .09, β = .08), whereas gratitude at T1 did not predict influence at T2. Figure 3 Path Model Examining the Longitudinal Relationships between Gratitude and Structural Job Resources. Standardized coefficients. Significant paths are depicted as solid lines. Non-significant paths are represented by dotted lines.   The Relationships between Employees’ Gratitude and Job Crafting The third model assessed the relationship between employees’ gratitude and job crafting. The proposed model (see Figure 4) had very good fit indices, χ2(6) = 6.72, p = .34, CFI = 1, SRMR = .03, RMSEA = .02, p = .71, 90% CI [.00, .08]. All variables at T2 were significantly predicted by their counterparts measured at T1. The findings were only partially consistent with hypothesis H3, which assumed that there would be a positive longitudinal effect of job crafting on employees’ gratitude. Only one dimension of job crafting at T1 (i.e., increasing challenging job demands) significantly predicted employees’ gratitude at T2 (B = 0.27, z = 3.09, p < .001, β = .17). The other two dimensions of job crafting measured at T1 exerted no effect on employees’ gratitude measured at T2. The results regarding the effect of gratitude on job crafting were mixed (RQ1). Gratitude at T1 had a positive, but only marginally significant effect on increasing structural job resources at T2 (B = .06, z =1.92, p = .06, β = .12). Gratitude at T1 did not predict the other two dimensions of job crafting. Figure 4 Path Model Examining the Longitudinal Relationships between Gratitude and Job Crafting. Standardized coefficients. Significant paths are depicted as solid lines. Non-significant paths are represented by dotted lines.   The Mediating Role of Job Crafting in the Relationship between Employees’ Gratitude and Social Job Resources The fourth model, examining the mediating role of increasing social job resources in the relationship between gratitude at T1 and social resources at T2 (RQ2a), demonstrated very good fit, χ2(1) = 0.02, p = .88, CFI = 1, SRMR = .00, RMSEA = .00, p = .91, 90% CI [.00, .08] (see Figure 5). Social job resources at T2 were predicted by their T1 counterpart (B = 0.29, z = 3.59, p < .001, β = .28), by increasing social job resources at T1 (B = 0.37, z = 3.41, p < .001, β = .22), and by gratitude at T1 (B = 0.16, z = 2.21, p = .03, β = .15). However, increasing social resources at T2 was positively associated only with its counterpart measured at T1 (B = 0.58, z = 10.84, p < .001, β = .56). As gratitude at T1 did not predict increasing social job resources at T2, mediation could not occur. Figure 5 A Half-longitudinal Mediation Model Examining the Explanatory Role of Job Crafting in the Relationship between Gratitude and Social Job Resources. Standardized coefficients. Significant paths are depicted as solid lines. Non-significant paths are represented by dotted lines.   The Mediating Role of Job Crafting in the Relationship between Employees’ Gratitude and Job Resources The fifth model assessed the mediating role of increasing structural job resources in the relationship between gratitude at T1 and structural job resources reported by employees at T2 (RQ2b). The model, displayed in Figure 6, demonstrated very good fit to the data, χ2 (1) = .42, p = .51, CFI = 1, SRMR = .01, RMSEA = .00, p = .64, 90% CI [.00, .13]. However, only the autoregressive paths were significant. Structural job resources at T2 were not predicted by either gratitude or increasing structural job resources at T1. Gratitude at T1 did not significantly predict increasing structural job resources at T2. Mediation was therefore not possible. Figure 6 A Half-longitudinal Mediation Model Examining the Explanatory Role of Job Crafting in the Relationship between Gratitude and Structural Job Resources. Standardized coefficients. Significant paths are depicted as solid lines. Non-significant paths are represented by dotted lines.   The aim of the present study was to examine the relationships between employees’ gratitude, job resources, and job crafting over time. More specifically, we tested whether there might be a positive and reciprocal relationship between gratitude and job resources, as well as between gratitude and job crafting behaviours. Furthermore, we explored whether job crafting might be an explanatory mechanism in the relationship between gratitude and job resources. Gratitude and Job Resources (H1 & H2) Our results suggest that there are no reciprocal relationships between gratitude and social job resources. Job resources at T1 did not predict employees’ gratitude at T2 (H1a), although employees’ gratitude at T1 predicted more social job resources three months later (H2a). The finding that gratitude led to more social resources is consistent with previous theoretical (e.g., Algoe, 2012; McCullough et al., 2001) and empirical (e.g., Chen et al., 2021; Feng & Yin, 2021; Nicuta et al., 2022; Wood, Maltby, Stewart, et al., 2008) work suggesting that gratitude facilitates the process of building and maintaining social relationships in different contexts, including the workplace. However, the question remains as to why social job resources at T1 were not a significant predictor of employees’ gratitude at T2. A couple of explanations can be put forward. First, our results suggest that social job resources are not very stable across time. Therefore, it could be argued that the time interval between the two study waves was too long for social job resources at T1 to exert an effect on employees’ gratitude three months later. Second, it might be that the effect of received social support on employees’ gratitude is contingent upon their individual need for help and assistance. A study conducted by Lee et al. (2019) showed that employees are more likely to express gratitude when they specifically asked others for their help. When assistance was proactively provided, employees were less likely to express appreciation to their helpers. These previous findings might also explain why the effect of social support from colleagues on employees’ gratitude was negative (although only marginally significant). It is possible that employees could sometimes perceive the help they receive as reflecting other people’s lack of trust in their abilities to independently solve work-related tasks. Therefore, social support might, under certain conditions, jeopardize employees’ need for autonomy, resulting in decreased gratitude. Contrary to our expectations, no reciprocal relationship was found between employees’ gratitude and the structural job resources they reported. The results suggested that gratitude prospectively predicted more opportunities for development and more skill variety (the latter result being only marginally significant), but not more influence (partially in line with H2b). On the other hand, none of the three structural job resources measured in this study predicted employees’ gratitude three months later (providing no support for H1b). These results seem in line with the idea that gratitude is a positive emotion that broadens employees’ attention and cognition (Fredrickson, 2004). Consequently, employees who are thankful for their work environment become more mindful of the resources that are available in their organisations. Moreover, they might be more motivated to give back to their organisations by creating more job resources. In this respect, it seems logical that gratitude differentially relates to various structural job resources. Whereas some resources might be more easily modified by employees’ actions (e.g., opportunities for development), others (e.g., the amount of influence or control the employees have over their work) are more dependent on relatively fixed factors, such as employees’ positions in the organisation. At first glance, the fact that influence, opportunities for development, and skill variety did not predict employees’ gratitude seems to indicate that these specific job resources are not particularly important in determining the amount of appreciation employees feel in their workplace. However, this result might also be attributable to the time interval between the two waves. Future longitudinal research might consider reducing the time lag between the measurements, in order to be able to better capture the potential effect of job resources on employees’ gratitude. Gratitude and Job Crafting (H3 & RQ1) Lending partial support to H3, the analyses revealed that only one of the three job crafting dimensions at T1 (i.e., increasing challenging job demands) positively predicted employees’ gratitude at T2. This result seems to suggest that, in the process of taking on additional responsibilities that stimulate their professional development, employees find more reasons to appreciate their work environment. For example, such challenging job demands might give employees the opportunity to make use of their skills, collaborate with others, and receive recognition for their achievements – all of which might lead to employees’ increased gratitude for their jobs. This finding is also in line with previous studies suggesting that job crafting behaviours have a beneficial effect on employees’ attitudes towards the work environment (see Rudolph et al., 2017, for a meta-analysis). Future studies might explore the mediating mechanisms for the effect of increasing challenging job demands on employees’ gratitude. As suggested by previous research (e.g., Toyama et al., 2022; L. Wang et al., 2022), the satisfaction of employees’ basic psychological needs might be one of the explanatory mechanisms in this relationship. Regarding the prospective effect of gratitude on employees’ job crafting (RQ1), the results indicated that gratitude at T1 did not predict increasing social job resources and increasing challenging job demands, but had a marginally significant and positive effect on increasing structural job resources. This finding should be interpreted with caution, but seems to suggest that thankful employees might be more inclined to develop their skills and to gain more knowledge and autonomy in their jobs, potentially as a way to reciprocate for the benefits they receive from their organizations. Taken together, these mixed findings are only partially consistent with the idea that gratitude promotes employees’ proactivity in the form of job crafting (Chen et al., 2021) and draw attention to the fact that cross-sectional studies could potentially paint an overly optimistic image of the benefits of gratitude in the workplace. More longitudinal and experimental studies are needed in order to be able to draw definitive conclusions on the effect of gratitude on job crafting behaviours. Moreover, future studies might also consider examining how “episodic” gratitude relates to job crafting, using the experience sampling methodology. Such studies could also investigate whether episodic gratitude predicts job crafting behaviours over and above the effect of positive emotions in general. The Mediating Role of Job Crafting (RQ2a, b) Our results further indicated that job crafting did not account for the relationship between gratitude and job resources. Hence, more research is needed in order to examine the mediating mechanisms underlying these relationships. Regarding the relationship between employees’ gratitude and social resources, the most straightforward explanation appears to be linked to the heightened prosocial tendencies of thankful individuals, as outlined in the introduction (e.g., McCullough et al., 2001). Previous studies showed that grateful employees are more likely to engage in behaviours aimed at proving assistance to their colleagues, compared to their less grateful counterparts (e.g., Kersten et al., 2022; Sawyer et al., 2022). In turn, such prosocial acts might help grateful employees benefit from more social support when needed (for example, from the persons they helped in the past). It might also be that grateful employees express their appreciation to their colleagues more often. This might make others perceive them as more responsive and consequently be more willing to affiliate with them (i.e., the witnessing effect of gratitude; Algoe et al., 2020). Further, the association between gratitude and structural job resources could be explained by the fact that grateful employees have more supportive and/or larger social networks, which facilitate their access to structural resources that would otherwise have been out of reach. Another possibility could be that grateful employees benefit from opportunities in the workplace because they are more positively evaluated by others due to the altruistic behaviours they exhibit (Rosopa et al., 2013). Theoretical and Practical Implications Our research adds to the existing body of literature by being the first to investigate the relationships between gratitude, job resources, and job crafting using a longitudinal design. Unlike most previous studies, which focused on the outcomes of gratitude in the workplace, we were also interested to examine the predictors of employees’ thankfulness. This study expands our understanding of the factors that influence employees’ gratitude by suggesting that one dimension of job crafting (increasing challenging job demands) leads to more gratitude over time. From a practical standpoint, this finding suggests that implementing job crafting interventions, which were already shown to improve important outcomes such as work engagement and contextual performance (see Oprea et al., 2019 for a meta-analysis), might also have a positive effect on employees’ gratitude. Our research also points to the fact that fostering a sense of gratitude among employees could prove beneficial for organisations, as thankful employees seem to be more aware of the resources that are present in their work environment. Efforts geared towards enhancing employees’ gratitude could include human resources initiatives such as appreciation programs (i.e., programs that recognize and reward employees for their hard work and achievements; Fehr et al., 2017) or interventions consisting of various exercises that might help employees become more aware of the positive aspects of their jobs (e.g., gratitude lists, behavioural gratitude expression; Komase et al., 2019). Limitations and Future Directions A number of limitations of the present research should be noted. First, the relatively small sample size used in this study lowers its statistical power and could lead to false-negative results. Second, due to the exclusive reliance on self-report questionnaires, common method bias could arise and artificially inflate the associations among the variables (Podsakoff et al., 2012). However, in this study, self-report questionnaires were considered to be a better option than other-report measures, seeing that the employees are probably more accurate in evaluating their level of gratitude and job crafting than their colleagues or supervisors. Third, we employed a two-wave longitudinal design. Although this design is very commonly used in organizational psychology (e.g., Buri et al., 2019; Muntz & Dormann, 2020; Spagnoli et al, 2021) and is superior to cross-sectional research in that it may suggest the temporal order of events, some authors suggest that the minimum number of waves in a longitudinal design should be three (e.g., Ployhart & Vandenberg, 2010). Consequently, future research could consider employing a three-wave longitudinal design when examining the relationships between gratitude, job crafting, and job resources, particularly if researchers are interested in exploring potential mediators. Fourth, although our data suggests that gratitude precedes job resources, no causal inferences can be made. Experimental studies are needed in order to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. Fifth, despite using a diverse sample, with employees from diverse industries, our participants can be described as “white-collars”. The results might not extend to employees performing mostly physical labour. Future studies could examine how gratitude relates to employees’ job crafting and job resources in samples of blue-collar workers, using scales that were specifically designed for this category of employees (e.g., Nielsen & Abildgaard, 2012). Conclusion The present study provided preliminary insight into how employees’ gratitude relates to job resources and job crafting over time. Although we found no evidence for bidirectional relationships between these variables, this research broadens our knowledge of the potential antecedents and outcomes of gratitude in the workplace. Importantly, the results suggest that increasing employees’ gratitude could help them perceive or even generate more resources in their organisations, a finding which bolsters the case for developing and testing gratitude interventions that could be incorporated into organizational practice. More work is necessary in order to determine the mediating mechanisms in the relationship between thankfulness and resources in the workplace. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Authors’ Contribution The first two authors contributed equally to this work. Notes 1 We opted for a three-month interval between measurements to facilitate a meaningful comparison of our results with those presented by Wood, Maltby, Gillett, et al. (2008), who assessed the prospective effect of gratitude on social resources using a similar lag between the measurements. 2 The following R packages were used: dplyr (Wickham et al., 2023), flextable (Gohel & Skintzos, 2023), foreign (R Core Team, 2022a), Formula (Zeileis & Croissant, 2010), ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), Hmisc (Harrell Jr., 2022), kableExtra (Zhu, 2021), knitr (Xie, 2015), lattice (Sarkar, 2008), lavaan (Rosseel, 2012), mvtnorm (Genz & Bretz, 2009), papaja (Aust & Barth, 2022), PerformanceAnalytics (Peterson & Carl, 2020), psych (Revelle, 2022), rstatix (Kassambara, 2023), sasLM (Bae, 2023), survival (Therneau & Grambsch, 2000), tinylabels (Barth, 2022), xts (Ryan & Ulrich, 2022), and zoo (Zeileis & Grothendieck, 2005). Cite this article as: Nicuta , E. G., Opariuc-Dan, C., & Constantin, T. (2024). Gratitude, job resources, and job crafting: A two-wave longitudinal study on a sample of Romanian employees. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(1), 19-30. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a2 Funding: This paper was supported by the Romanian Industrial and Organizational Psychological Association (APIO) through the “Horia Pitariu” Research Scholarship, awarded to the first author. The data and code used to generate the results presented in this paper are openly available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VSJAH References |

Cite this article as: Nicuta, E. G., Opariuc-Dan, C., and Constantin, T. (2024). Gratitude, Job Resources, and Job Crafting: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study on a Sample of Romanian Employees. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(1), 19 - 30. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a2

Correspondence: gabriela.nicuta@yahoo.com (E. G. Nicuta).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef